In the glossy marketing materials, the building gym is immaculate. There are floor-to-ceiling mirrors, brushed steel machines that shine like props from a futuristic fitness film, and enough square footage to suggest you might, at last, become the kind of person who “doesn’t need a real gym membership.” The leasing agent, with her rehearsed smile, pushes open the glass door and gestures as if she’s unveiling the Sistine Chapel. It is “state-of-the-art,” she says, as though the phrase alone will strengthen your core.

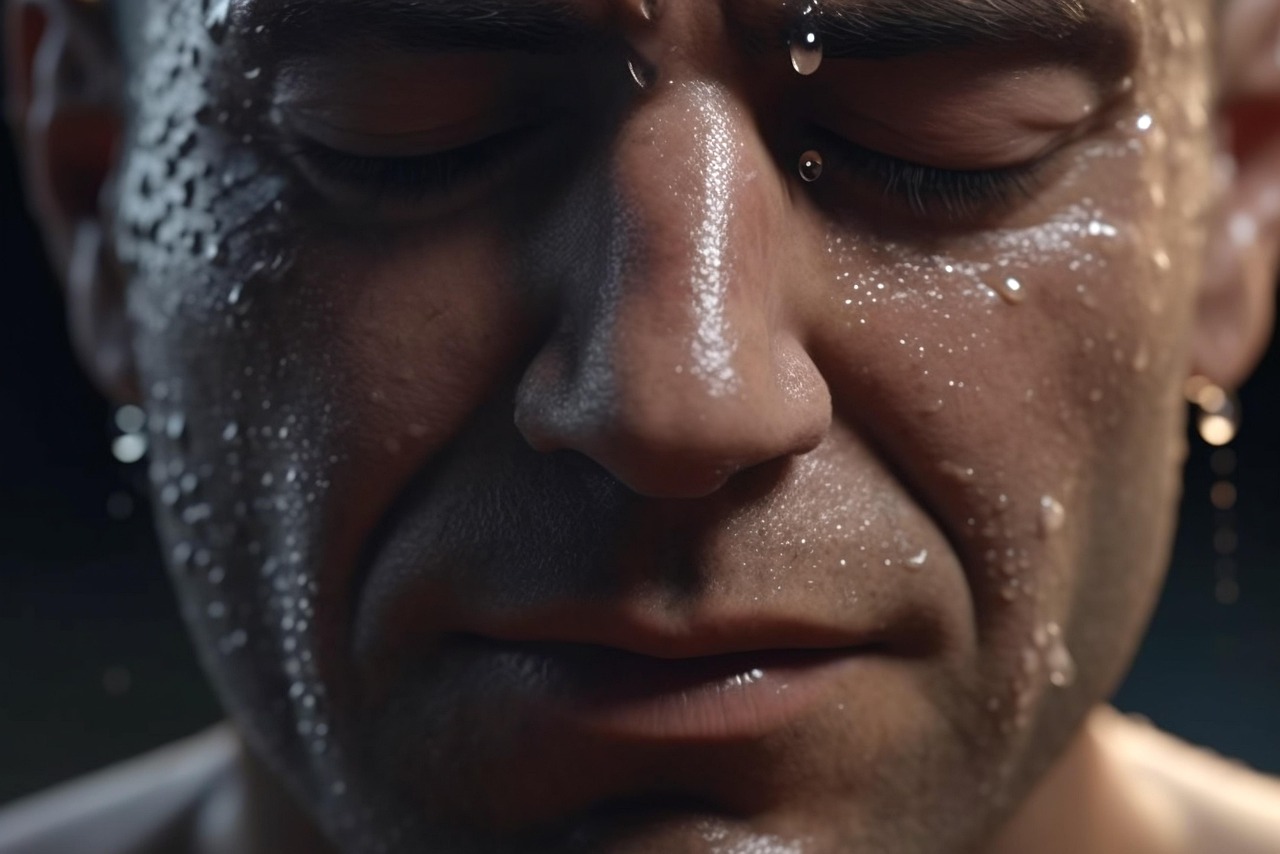

But a few days after moving in, you discover the fine print—though it never appears on the lease. The gym is hot. Not “working-up-a-sweat” hot, but “indoor tomato hothouse” hot. Seventy-five degrees, sometimes more, with humidity clinging at sixty percent, as if the thermostat has been set by a mischievous botanist. Within five minutes of cardio, your skin is glazed, your clothes soaked, and the cheerful marketing image dissolves into the kind of fever dream normally reserved for survival films. The treadmill is less a machine than a conveyor belt toward collapse.

The first time you complain, you assume it’s a simple oversight. Perhaps the cooling system broke. Perhaps someone forgot to turn a dial. But then you hear the doorman confirm, with a shrug, that the gym “is always like that.” Other tenants, he explains, have raised the same concern. They too wanted air, something less tropical, but the answer is always evasive. Management has “looked into it.” Management is “aware.” Management will “circle back.” The temperature, like management’s indifference, remains constant.

Brodsky Management: Action Must Be Taken

The company behind the building, Brodsky Management, operates more than forty luxury properties across New York City. It is an empire built on glossy promises: river views, rooftop terraces, gyms that shimmer in photographs. But tenants here would be grateful for something less glamorous and more practical—air that does not resemble a greenhouse.

It would not take much. A small adjustment to the thermostat, a little less humidity, a nod to the health guidelines everyone else seems to follow. It is the kind of gesture that would transform the gym from a running joke into an actual amenity. Residents are still waiting, still sweating, still hoping Brodsky will finally notice that “luxury” should not mean training for a marathon in the tropics.

Fitness guidelines suggest that gyms be kept around sixty-eight degrees—a temperature that encourages exertion without encouraging collapse. In cooler air, muscles recover, bodies last longer, and treadmills are not mistaken for endurance tests in the Everglades. But this building has opted for its own philosophy: if residents are sweating, the gym must be working. Science is no match for the shrug of a landlord.

What makes it worse is the sense of theater. Prospective renters are still led on tours through the space, where the machines glisten under lights and the temperature—helped by the door propped open for ten minutes—momentarily passes as tolerable. There is no mention of the climate inside, no note in the brochure advising future tenants to bring electrolytes and possibly an oxygen mask. The room looks perfect, provided you do not attempt to use it.

Still, the gym issue has become a favorite subject of building small talk. In the elevator, one resident asks another if she’s tried working out lately. They laugh, they roll their eyes, they describe the stifling air and their dripping clothes. It becomes a form of solidarity: a club of tenants bonded not by fitness but by futility. They write emails to management and swap the identical, vague replies. They speculate on who exactly controls the thermostat and why it is apparently protected like a national secret. They joke about sneaking in with a screwdriver, though everyone knows they never will.

And yet, despite everything, the gym continues to anchor the building’s idea of itself. This is a “luxury tower,” after all, one of dozens operated by a large management company whose name rarely appears in the complaints but is muttered often in private conversations. The gym is part of the sales pitch, the gleaming amenity that justifies the rent.

Conclusion

It is, in its way, a perfect symbol of New York luxury living. The promise is always larger than the delivery. The rooftop has a view, but no chairs. The pool exists, but the water is teeth-chattering. The gym is open, but it doubles as a sauna. Amenities are less about use than about optics, and optics, as every tenant learns, are the one thing landlords reliably provide.

And so the space continues, humid and unwavering. The mirrors fog, the air thickens, and residents sweat together in a room designed for comfort but delivered as endurance. It is marketed as a place of strength but functions as a lesson in resignation. This is luxury in New York: a glossy promise, a sweaty reality, and a chorus of tenants waiting for a thermostat that never turns.

Born and raised amidst the hustle and bustle of the Big Apple, I’ve witnessed the city’s many exciting phases. When I’m not exploring the city or penning down my thoughts, you can find me sipping on a cup of coffee at my favorite local café, playing chess or planning my next trip. For the last twelve years, I’ve been living in South Williamsburg with my partner Berenike.